The Thinking Path

INTRODUCTION

The CEO of a bottling company toured a plant whose employees were demoralized. The tour proved extremely successful, and the CEO’s approval of what he saw generated a visible lift of mood. Once the CEO had departed, the plant manager addressed the employees: “The boss really liked what he saw. He said it was the best he had ever seen. But why did you have the order of the products reversed in the coolers? It was embarrassing!” The employees’ mood instantly slumped.

Afterward, a colleague asked the plant manager why he dwelled on the negative. He replied: “They won’t be motivated toward perfection if you don’t keep finding something they did that they can improve. You always have to find something wrong. Good feelings don’t drive productivity and performance.”

Sound familiar? Unfortunately, it is very common and examples like this litter the organizational landscape.

This chapter presents a framework called the Thinking Path that is useful in leadership coaching and that can be used to help leaders understand and manage situations like the one described above.

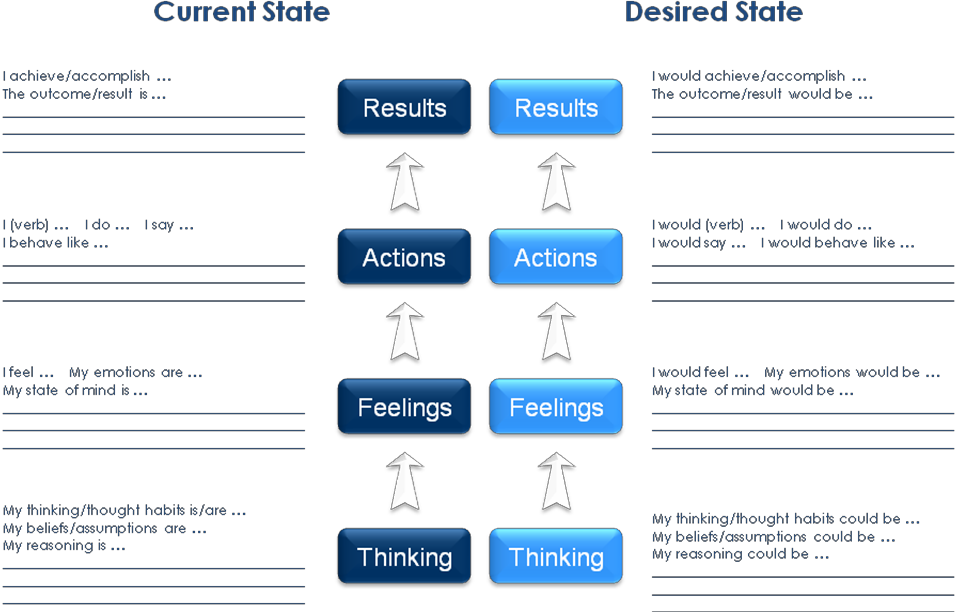

The Thinking Path stipulates that people’s conscious and unconscious thought processes (their thinking) generate emotional/physical states (their feelings), which in turn drive behaviors (their actions) that produce outcomes (their results). Figure 1 illustrates the Thinking Path framework.

Three questions inspired the creation of the Thinking Path:

How do human beings change?

What causes sustained change in human beings?

Why do some individuals succeed in changing their behaviors and results, and why do others fail?

The answers to these questions came to me after years of study, research, personal work, and client engagements all over the world. And the answers pointed to a deeper phenomenon called thinking and the impact of thinking on our moment to moment experience of life.

The Thinking Path provides a simple, yet powerful framework to help clients understand and work with their thinking in a way that can yield three outcomes:

Clients realize that their thinking is linked to their feelings and that by changing their thinking, their feelings also change.

Clients realize that their thinking and feelings drive their actions and results and that by changing their thinking and feelings, their actions shift and their results change.

Clients take greater responsibility for generating sustained improvements in their actions and results by intentionally shifting their thinking and their feelings.

This story and explanation of The Thinking Path by Alexander Caillet was published as a chapter in the book ‘Becoming a Leadership Coach’.

We have been engaging our clients in this approach for over 20 years with great results. If you are interested in learning more about The Thinking Path, let us know.

FROM THINKING TO RESULTS

Most observers would agree that the plant manager’s speech (his action) produced lower employee morale (his result). To the plant manager, however, the speech felt “right” and he delivered it intentionally to produce the exact outcome that was experienced and witnessed by all. Interestingly, a month earlier this same individual had received fairly negative feedback about these types of behaviors on his 360-degree performance review. And although this was the first time the organization had deployed a 360-degree feedback program, it was not the first time he had heard this feedback. And it was not the first time he had been told that these behaviors could damage his career.

What could a coach do to help this plant manager and how could the Thinking Path be of service? The obvious answer is that the coach would help the plant manager avoid producing such negative results by shifting his actions. To achieve this, the coach would help him change the source of his actions and results: his thinking and feelings.

Consider that the origin of the plant manager’s actions lies in his thinking. His answer to my colleague’s question makes his thinking visible: “You always have to find something wrong. Good feelings don’t drive productivity and performance.” Furthermore, my colleague noticed that just prior to making his statement the plant manager appeared anxious and impatient. The Thinking Path framework suggests that these feelings of anxiety and impatience were a product of his thinking.

THINKING

Human beings think. We think all the time. It is a central factor in our lives; our experience of reality is shaped by the moment-to-moment flow of our thoughts. One way to define thinking is as the reception and processing of external and internal data in order to assess and interpret the world within and around us. Of course, thinking also encompasses the much broader phenomena of human consciousness or awareness. Because of my long study of neuroscience, however, I am inclined to emphasize the cognitive aspect of thinking and the functioning of the brain that underlies it.

It is said that the human body—not only the brain but also the nervous system and all the sensory apparatus connected to it—processes billions of bits of data every minute. These data are received through our senses and are processed, interpreted, and put to use. New data are received, stored, and held as archival memory for later use. Familiar data are matched to the archival memory information in order to be understood.

The brain’s primary function is to receive and store data within its networks and to activate specific networks once the data is presented. From the moment our brain is formed in the fetus, it uses the neurons resident within the brain to begin the process of coding the data it receives by creating neural pathways within predisposed regions of the brain. When specific units of data—such as a visual image, a sound, an odor, or a physical sensation—are received repeatedly throughout one’s life, specific neural pathways corresponding to these units of data become stronger, creating hard-wired paths of neural circuits. From this point on, when data are presented to a human being, the brain responds by activating or “firing” specific neural pathways across the various regions of the brain that are predisposed to interpret these data. These neural pathways provide a perception of the data, which can then be interpreted and understood. This process occurs continuously in real time, providing us with the ability to make sense of our surroundings.

The advantage of thinking is that we can use what we already know to make sense of confusing and complex data instantly. As we do this, we create meaning, make decisions, and then take action.

Thinking is what allows us to function and produce results.

Thinking is highly complex phenomenon, and it would be impractical to provide a comprehensive review of all that is known about it in this chapter. I also find that most clients are not interested in such a review and seek a simple and practical way to work with their thinking. To this end, I would like to introduce a short-hand, nonscientific, and practical term, thought habits, that allows clients to work with their thinking in terms of specific units of thought such as beliefs, knowledge, perceptions, assumptions, conclusions, etc.

From the womb and throughout our lives, we constantly acquire new thought habits as a result of our ongoing experiences. The more we experience, the more data the brain codes. The more the brain codes, the more thought habits we have. The more thought habits we have, the more we can perceive and interpret. In the end, we develop a large storehouse of thought habits that allows us to process and interpret vast amounts of data.

In the case of the sales manager, the thought habit in play was: “You always have to find something wrong. Good feelings don’t drive productivity and performance.”

FEELINGS

One way to define feelings is as emotional and physiological manifestations experienced throughout the body. There is a great deal of debate as to which comes first, thinking or feelings. I believe thinking occurs first and feelings follow. This is supported by research that points to the fact that data is processed first in the brain and in the body triggering key organs within the center of the brain that, in turn, launch a series of chemical reactions that occur within the body to create emotional and physiological reactions.

As such, feelings provide the most reliable indicator of the characteristics of the thought habits we are generating. Insecure, chaotic, resentful thought habits generate feelings of anxiety, confusion and anger; secure, focused, composed thought habits generate feelings of clarity, calmness, and confidence.

Note that the plant manager had observable feelings—anxiety and impatience—prior to blurting out his statement. Upon further investigation, my colleague learned that as the morning went on, he began to feel anxious that the event was becoming “too much of a mutual admiration event,” and he felt a need to reign in the group. To him, his feelings of anxiety were a normal consequence of the CEO’s very positive remarks. This justified his negative statement to the workers. As he perceived the events unfolding, he was matching the incoming data to what he had archived in his brain from the past:

“Good feelings don’t drive productivity and performance.” He did not realize that his own thought habit was triggering a feeling.

The challenge is that much of the time we do not notice our thinking. By contrast, we do feel our feelings as they become manifest as emotional and physiological reactions. So we may believe that our feelings are causing us to act in certain ways, but actually we are being driven by our thought habits.

It is important to understand that it is the combination of our moment-to-moment thinking and feelings that create what we experience as reality. Whether or not we have interpreted the data correctly does not matter; our inner experience feels like reality.

The Thinking Path helps clients understand the mechanism that generates what they perceive as reality. This is important because an individual’s subjective reality may not reflect the objective situation.

Instead, it might be based upon thought habits that are questionable, unnecessarily negative, or simply untrue. If a client’s reality is based upon such thought habits, he/she may take actions that produce undesirable results.

ACTIONS AND RESULTS

One way to define actions is as the behaviors we manifest in the form of what we say and do. Our actions lead to results, which can be defined as the outcomes and achievements we produce. So each action we take produces results, and it is on the basis of our actions and results that we ultimately are assessed.

In the case of the plant manager, the action was a statement: “But why did you have the order of the products reversed in the coolers? It was embarrassing!” The result he produced was a mood of disempowerment and resignation among the workers. He may not have seen the connection between action and result, but it was unmistakable from the observer’s standpoint.

COACHING WITH THE THINKING PATH

Coaches can use the Thinking Path in their coaching sessions to help their clients gain a much deeper and clearer understanding of what is at the source of the issues and challenges they are facing and to define different scenarios that will generate sustainable improvements regarding these issues and challenges. The Thinking Path methodology requires clients to explore what is happening in the issue and challenge they are facing by completing a Current State Thinking Path including results, actions, feelings, and thinking. They then imagine a more desirable scenario and complete a Desired Current State Thinking Path.

To accomplish this, coach and client can use the Thinking Path template provided in figure 2 below. The instructions are simple:

The client selects a real issue or challenge.

With the guidance of the coach, the client identifies his/her thinking, feelings, actions, and results as they are occurring presently in the issue or challenge—this is the current state.

The client also defines his/her thinking, feelings, actions, and results as they could be—this is the desired state.

Coach and client may begin with either the current or desired state, and jump back and forth if they wish.

Coach and client may begin at any level of the Thinking Path within both the current and desired states and proceed through the other levels using any sequence they wish.

Coach and client may use the starter phrases provided above the blank lines in the template.

The client may choose to write his/her responses down in the blank spaces or simply speak them.

Figure 2: The Thinking Path Template

a .pdf of Figure 2 for your convenience

A coaching session using the Thinking Path may take 30 minutes to several hours and may occur over the course of several sessions. Figure 3 below provides an example of an executive who completed both the current and desired states during several coaching sessions. This 38-year-old leader engaged in coaching due to recent criticism of his performance as a manager with the organization and due to his deteriorating health. He found the sessions challenging but made the discovery that underlying his actions and results was a set of thought habits—which he called core beliefs—he had never before seen with such clarity.

As stated above, coaching with the Thinking Path can yield solid results. Yet, it is important to remember that this is only a framework, and like any framework, it best serves those who invest in study and practice, and it will not be appropriate in every situation. Therefore, give yourself time to learn how to use the Thinking Path.

Try it on yourself first and with a person in your life who is not a client and who is willing to experiment with you. When you try it for the first time with a client, apply it to an issue or challenge that is not too complex; you can apply it to more complex issues later on after you have gained experience with the model.

When you begin using the Thinking Path with clients, remain alert to the client’s responsiveness and reactions. If the client seems disinterested or is resisting the approach, be ready to let go of the framework. You may choose to come back to it later or drop it altogether. The key is to remain flexible and to always meet your client where he/she is.

CHANGING THINKING

Up to this point, the Thinking Path has provided us with an effective approach to understand our current state and define our desired state. It has allowed us to peer into our thinking and identify the thought habits that we use today and those we wish to use tomorrow. But is this enough to help our clients really change their thought habits? The answer is no. In my experience, most clients need something more to help them change their thought habits in a sustained manner. What they need is an action plan comprised of a set of goals and practices that transform the desired state into reality.

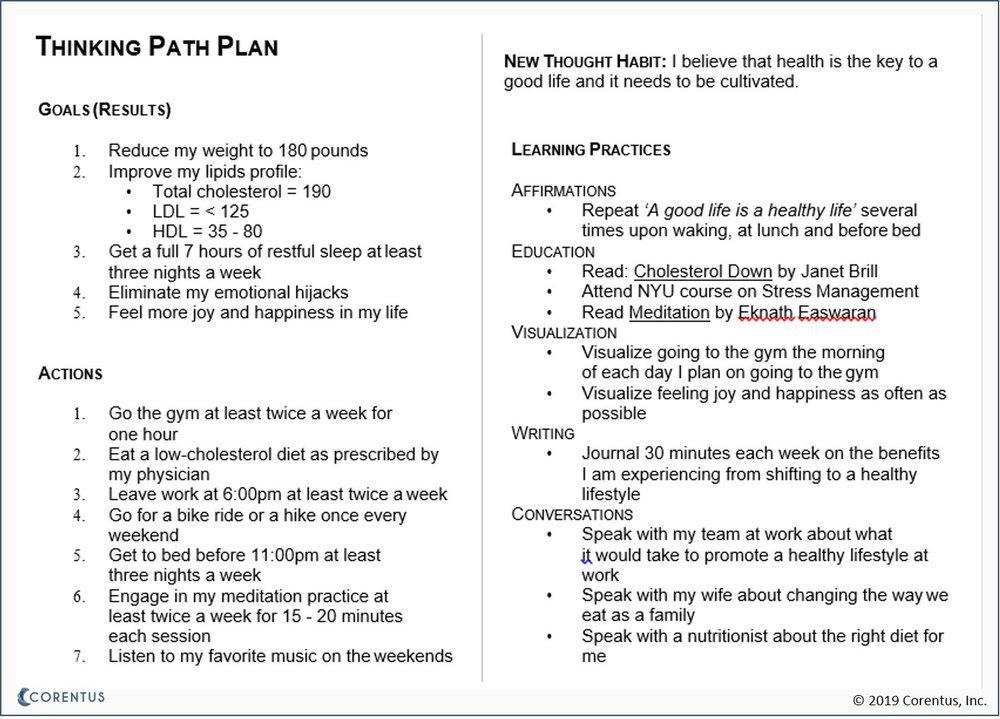

Most coaches know how to build action plans and most clients appreciate action planning. However, when most coaches build action plans they focus primarily on behaviors and results and construct a set of goals related to the new results and a set of behaviors to achieve these results. For most coaches and clients, this may feel like enough. I believe it is not as too often simply setting a new goal and identifying new behaviors to reach the goal leads only to short-term, unsustainable shifts. The New Year’s resolution is the most glaring example of these types of shifts. What is needed is another action plan aimed at sustaining the new thinking described in the desired state—an action plan that can ensure that the necessary change in thought habits actually does occur. We call this action plan a Thinking Path Plan; it is a combination of traditional planning oriented toward behaviors and results and planning focused on the thought habits in order to enhance the possibility of sustained change.

Fortunately, we can change our thought habits if we choose to do so, and we can do so throughout our entire lives. New research in neuroplasticity confirms this statement. We now understand that the brain’s primary function of receiving and storing data within its networks continues throughout our lives. As such, the brain can create new neural pathways within predisposed areas of the brain based on new data. These new pathways can be built in addition to the original neural pathways and over time can become stronger than the old pathways, providing us with alternatives. These alternatives are critical for a very important reason: the brain does its work extraordinarily quickly and it is impossible to intercept the firing sequence of specific neural pathways in response to data. As such, our interpretations are almost immediate. That said we can choose to keep or change the thoughts we have made, once we have made them. And if we choose to change the thought habit, we can select the alternative. And if we consistently choose the alternative, we have the possibility of quieting down the original pathways or extinguishing them altogether. As long as we can learn we can acquire new thought habits and even change or eliminate old thought habits.

A question now emerges: How do we encode the new thought habits from the desired state into our neural pathways so that they become viable alternatives the next time the original pathways fire? Not surprisingly, we must engage in an activity most of us experience throughout our lives: learning. It is through learning that we discovered our A, B, and C’s, 1, 2, 3’s and do, re, mi’s. It is through learning that we acquired most of our thought habits. And it is through learning that we can encode new thought habits into our neural pathways so that they become viable alternatives

There are many approaches used in learning, and everyone has a preferred approach that works best for the individual. When using the Thinking Path, there are five approaches that are particularly helpful in creating new and sustained neural pathways: (1) repetition, (2) education, (3) visualization, (4) writing, and (5) conversation. Most clients will want to use more than one approach, but may not use all five at once.

REPETITION

Repetition, also known as affirmation, involves repeating new thought habits like mantras. In the same manner we memorized our multiplication tables, the act of repeating a thought habit increases the chances that it will be encoded in our brains. In neuroscience, this is called long-term potentiation and can be described as a long-lasting period of signal transmission between two neurons that increases the strength of their connection to one another and thus the probability that they will fire together in the future. Long-term potentiation is widely believed to be at the basis of learning and memory building and has led to the well-known adage that neurons that fire together wire together.

With this in mind, a coach might suggest that as part of a client’s Thinking Path Plan, the client could quietly affirm a new thought habit several times a day. The client could continue to do this until he or she experienced greater facility in choosing the new thought habit as an alternative to the original, and/or began to feel or act differently when he/she affirmed the new thought habit. Let’s now take the case of the executive in figure 3 and focus for the rest of this chapter on building a Thinking Path Plan to encode and sustain one of his four new thought habits: “I believe that health is the key to a good life and it needs to be cultivated.” If we focus on repetition, one part of his Thinking Path Plan could be to affirm this thought habit every morning, afternoon, and evening for a period of time.

One challenge to be aware of is that some clients will give up on repetition because it may seem artificial and shallow to them. The new thought habit may seem foreign, questionable, or simply untrue, and affirming it over and over again may not yield results. As such, repetition works best when it is coupled with other learning approaches that will give it a greater chance of becoming encoded as a new neural pathway and become the basis for a new reality.

EDUCATION

I define education broadly to include any active engagement in activities such reading, watching TV, videos and film, listening to experts, going to events and shows, and attending workshops and courses. It goes without saying that one of the essential components of learning is the acquisition and processing of new data and information either individually or in collective settings. From a neuroscience perspective, when we actively engage in educational activities related to a new thought habit, we experience a significant increase in neural activation relative to that thought habit. The more complex and collective the activity, the more neural landscape we use, the more neural pathways are formed, and the greater likelihood that new thought habit is encoded and sustained.

With this in mind, a coach might suggest that as part of a client’s Thinking Path Plan, the client could read articles or books related to the thought habit, watch a specific documentary or film that incorporates the thought habit, or attend a specific lecture, course, or workshop that further expounded upon the thought habit. In the case of the executive in the example, another part of his Thinking Path Plan could be to read articles on exercise and fitness, watch a documentary on the adverse effects of stress, attend a course on stress management, or consult a nutritionist. If these practices were coupled with daily affirmations, the probability that the thought habit would be sustained would be increased.

VISUALIZATION

Visualization, also known as mental rehearsal, involves quietly thinking about a thought habit and imagining how it might play out in real life. Recent research has revealed that the brain responds similarly to the thought of an action and to the real action. Athletes who have submitted themselves to electromyography have demonstrated that when they mentally rehearsed their moves, the electrical currents sent to their muscles by their brains were similar to the impulses sent when they were physically performing the moves. These experiments demonstrate that whether an activity is mentally imagined or is actively performed, the same neural pathways are stimulated, the same physiological changes are present, and the neural pathways are ultimately strengthened.

With this in mind, a coach might suggest that as part of a client’s Thinking Path Plan, the client could take a few minutes during the day or evening and quietly visualize how a thought habit could play out in real life. This is especially powerful if the client has been doing daily affirmations of the thought habit and has engaged in various educational activities. In the case of the executive in the example, another part of his Thinking Path Plan could be to take a few minutes each day for a week to quietly visualize being at the gym, engaging in stress management practices, or living a joyful and happy life. The executive would effectively be imagining prior to acting. This would strengthen the impact of the affirmations and educational activities.

One challenge to be aware of is that most clients prefer to close their eyes when performing visualizations in order to avoid distractions. As a consequence, many may feel uncomfortable closing their eyes and performing visualizations during the workday or even during a coaching session in the workplace. It is important to allow clients to perform visualizations when they feel most comfortable and this may be in a place other than the workplace.

WRITING

Writing, also known as journaling, involves writing about the thought habit. The client can use the Thinking Path framework to write about the thought habit including where it comes from, what it means, what it feels like to use it, and what behaviors and results emerge when it is used. Much has been written on the benefits of journaling as a meditative and reflective practice including enhancing self-awareness and self-understanding, discovering meaning in specific events, making connections between different ideas and events, gaining perspective and clarity, and developing critical thinking skills. From the perspective of neuroscience, the act of writing activates a broader neural landscape and causes a multitude of neural pathways to form and fire around the new thought habit. Writing also translates the thought habit into a motor skill by activating a sequence of neurons which ultimately fire motor neurons that activate our skeleton, glands and muscles. This not only strengthens the original thought habit but encodes the sequence within the broader landscape of the body.

With this in mind, a coach might suggest that as part of a client’s Thinking Path Plan, the client could take a moment each week to journal about a particular thought habit using the Thinking Path framework as described above. In the case of the executive in the example, another part of his Thinking Path Plan could be to take half an hour every week to journal about the thought habit. The subject of the journaling could be specific to one aspect of living healthy lifestyles or it could be general. As you can imagine, if journaling is added to daily affirmations, educational activities, and occasional visualizations, the probability that the thought habit would be encoded and sustained is even greater.

One challenge to be aware of is that some clients do not enjoy writing, and many shy away from the practice of journaling. It is important to allow clients to find their own approach and rhythm, including the frequency and duration of their journaling periods. It is also important to accept that some clients will simply not do it.

CONVERSATION

Conversations with others about a specific thought habit can generate a remarkable amount of learning quickly. From the perspective of neuroscience, conversations, like writing, activate a broader neural landscape and cause a multitude of neural pathways to form and fire around the new thought habit. Conversations also translate the thought habit into a series of motor skills by activating several sequences of neurons which also ultimately fire motor neurons. This also encodes the sequence within the broader landscape of the body and strengthens the original thought habit. We often remember great conversations and their content. And if the client is willing to remain curious and open and to use inquiry and actively listen, he/she can only enhance the number of new neural connections that can be made relative to the thought habit.

With this in mind, a coach might suggest that as part of a client’s Thinking Path Plan, the client could select certain people in both the personal and professional spheres to have conversations with. These conversations could be about the thought habit itself or about applications of the thought habit in everyday life. In the case of the executive in the example, another part of his Thinking Path Plan could be to have specific conversations about his desire to live a healthy lifestyle with his wife, several friends, his doctor, and one or more of the experts he listened to in his education activities. He could also have conversations or even work sessions with his boss and his team about what it would take to engage in a healthy lifestyle at work. Conversations are an excellent way to transform affirmations, educational activities, visualizations, and journaling into an interactive experience. They can be powerful in their ability to sustain change.

One challenge to be aware of is that some clients are more reserved, may lack conversational skills, may be uneasy having these types of conversations, or may have issues speaking with certain people.

It is important to gain a clear understanding of any reservations a client may have and to strategize accordingly. There are many different ways to have conversations and many different types of people with whom to have conversations.

THE THINKING PATH PLAN

Let’s now examine how the Thinking Path Plan actually did support the executive. Figure 4 provides one of the Thinking Path Plans developed by the executive and his coach. This particular plan focuses on the executive’s health and lifestyle. When the executive and his coach began the action planning process, they completed a first level of planning focused on establishing a set of goals (results) to achieve the desired state and a set of actions to achieve these goals. These goals and actions are located on the left-hand side of the plan. The executive and his coach then selected the thought habit “I believe that health is the key to a good life and it needs to be cultivated” and developed a set of learning practices designed to fully encode and sustain this thought habit in order to more powerfully support the fulfillment of the actions and the achievement of the goals. These are located on the right-hand side of the plan. The full plan took two coaching sessions to complete.

Figure 4: Thinking Path Plan

a .pdf of Figure 4 for your convenience

And although it only took two sessions to complete the plan, it took several years for this executive to fully live a healthy lifestyle. The change was not immediate, and there were many relapses. Although neuroplasticity informs us that as long as we can learn, we can acquire new thought habits and even change or eliminate old thought habits, it does not inform us on the time it takes to do so. Changing our thinking can and, in most cases, will take time.

The good news is that the executive ultimately did change, and when he did, he was not just acting out a new healthy lifestyle; he was being a new healthy lifestyle. He believed in living a healthy lifestyle, and this new way of thinking led to significant changes in his life and had an impact not just on him, but also on his team at work and ultimately on his personal life at home. He continues this lifestyle to this day, making continuous improvements and enjoying the benefits he receives.

CONCLUSION

How do human beings change? What causes sustained change in human beings? Why do some individuals succeed in changing their behaviors and results, and why do others fail? These were the three questions that inspired the creation of the Thinking Path over 20 years ago. Today, hundreds of coaches and a multitude of clients from around the world have benefited from this simple yet effective framework. Many coaches describe it as an essential component of their coaching toolkit and one of the lenses through which they engage with their clients. Many clients speak of the deep insights they acquired and the sustained thinking and behavioral changes they made using it.

I have personally witnessed deep and lasting transformation in many leaders who have used the Thinking Path in their coaching work. Whether working in large corporations, small businesses, government institutions, NGO’s or nonprofit organizations, these leaders were able to clearly understand the current source of their limitations. They were able to recognize that their thinking is linked to their feelings and that by changing their thinking, they also change their feelings. They realized that their thinking and feelings drive their actions and results and that when they change their thinking and feelings, their actions shift, and their results change. And they took greater responsibility for generating sustained improvements in their actions and results by intentionally shifting their thinking and their feelings and creating new realities that better serve them and the people they serve.

— END.

Berns, G., PhD., Iconoclast: A Neuroscientist Reveals How to Think Differently. Boston: Harvard Business Press, 2010.

Charles, J. P. “Journaling: Creating Space for ‘I.’” Creative Nursing 16, no. 4 (2010): 180–184. Childre, D., and B. Cryer. From Chaos to Coherence. Boulder Creek: Planetary, 2004.

Claxton, G. Hare Brain, Tortoise Mind. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 2000.

Claxton, G. Noises from the Darkroom: The Science and Mystery of the Mind. London: HarperCollins, 1994.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. Finding Flow. New York: Basic Books, 1997.

Demasio, A. R. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: Putnam’s, 1994. Goleman, D., R. Boyatzis, and A. McKee. Primal Leadership: Realizing the Power of Emotional

Intelligence. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002.

Greenfield, S. A. Journey to the Centers of the Mind: Toward a Science of Consciousness. New York: Freeman, 1995.

Humphries, N. A History of the Mind: Evolution and the Birth of Consciousness. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992.

Kandel, E., Schwartz, J., Jessell, T., Siegelbaum, S. and Hudspeth, A., Principles of Neural Science, Fifth Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional, 2012.

LeDoux, J. The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996.

LeDoux, J., Synaptic Self: How Our Brains Become Who We Are. New York: Penguin Books, 2003. Mills, R. Realizing Mental Health: Toward a New Psychology of Resiliency. New York: Sulzburger &

Graham Publishing, 1995.

Ornstein, R., and D. Sobel. The Healing Brain: Breakthrough Discoveries About How the Brain Keeps us Healthy. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987.

McTaggart, L., The Intention Experiment. Harper Element: London, 2007. Rock, D., Your Brain at Work. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2009.